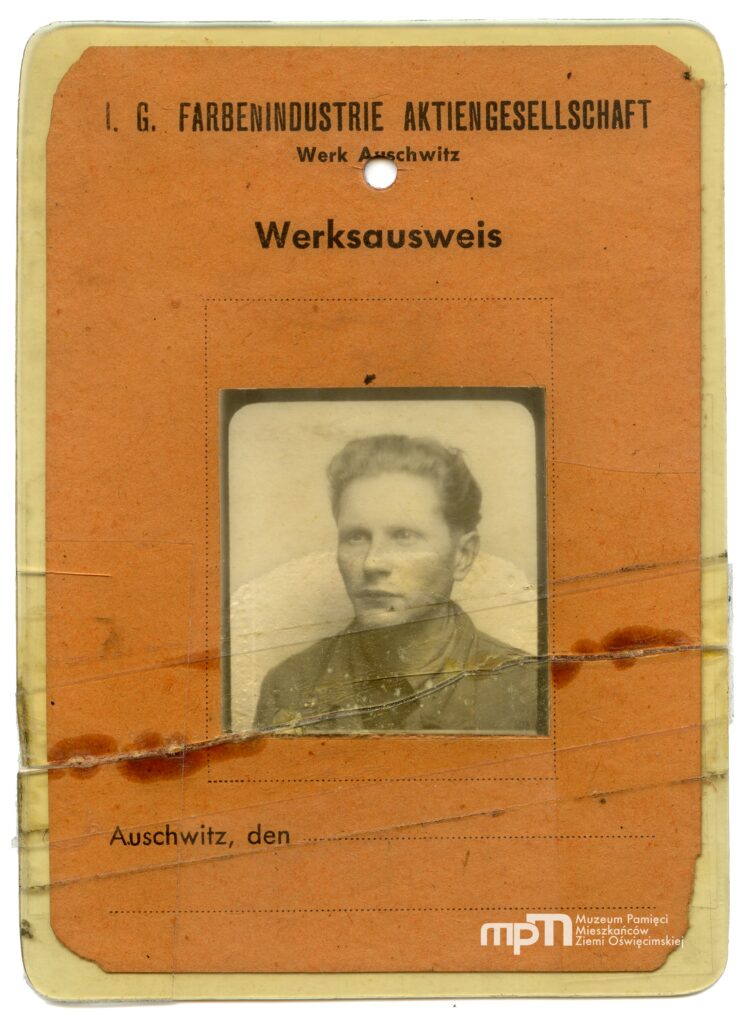

Teresa Bebak from Oświęcim has donated original documents of her father Jan Zajas from the German occupation and photographs of him to the Remembrance Museum’s collection. Could her father have been the Janek the electrician who helped Jewish women prisoners at KL Birkenau in 1944?

“Probably not found” read the title of Ms Bebak’s message to the Remembrance Museum.

“From reading Kącki’s “Black Winter”, I learned about a female prisoner who was looking for her benefactor from the war. Unfortunately, she undertook this search after my father’s death, as it would have been easier to verify the information earlier. However, everything points to the fact that it was him. You may find this of interest,” she wrote in her e-mail. She also quoted an excerpt from a book edited by Henryk Świebocki entitled “People of Good Will” dedicated to the events of 1944.

Merka meets Janek

Merka Szewach was born in 1926 to a Jewish family in Białystok. During the German occupation, she was sent to the Bialystok ghetto, then to Majdanek, Bliżyna and Auschwitz.

In Danuta Czech’s book entitled “Calendar of Events in KL Auschwitz”, page 719, under the date 31 July 1944, we find the following sentence: “From the RSHA transport from Bliżyna, which was a sub-camp of KL Lublin, 1,614 Jews were sent after selection to the camp as prisoners, with the numbers B-1160-B-2773, and 715 women, with the numbers A-15211-A-15925”.

This paragraph takes up 3.5 lines in the book, a book which contains the stories of more than two thousand human lives. Among them, Merka Szewach, whom the Germans brought to the Auschwitz death camp and then dehumanised by assigning the number A-15755.

“I met Janek in the B Lager at Birkenau in the Czech camp, as it was then called. I was in a very grave condition at the time, deathly starved, sickly, horrified by the monstrous conditions, without hope of any help or deliverance from this inhuman situation. Janek worked in the camp as an electrician, with two other Polish workers. He was about 22 years old at the time. He took an interest in my tragic fate, was full of compassion and wanted to help me,” recalls Merka in a letter published in the book “People of Good Will”. In KL Birkenau she was with three friends. “Janek, deeply shocked by our plight, brought us food, cigarettes that could be exchanged for bread, also items of clothing and he even brought me shoes, all at great risk”.

Thanks to the yeast smuggled by Janek, Lubka – one of Merka’s friends – survived. Janek became so involved in helping her that he began to devise an escape plan for Merka. However, the prisoners were moved to another location and the plan never came to fruition.

Maybe there is still a chance

Merka survived the war. After it ended, she changed her name to Miriam Yahav, married and settled in Israel.

All the time she hoped she would still meet her rescuer.

“I regret that I do not remember his name, but it is never too late to pay tribute to a man who was not indifferent to the suffering, humiliation and extermination of innocent victims in the “Age of Ovens” Maybe there is still a chance that I will be able to hug him in person, to thank him, because I often visit Poland with Israeli youth and we are always in Oświęcim, where I talk about my personal experiences, and at the Museum it is known that I am still looking for Janek,” she wrote in the aforementioned letter.

Merka/Miriam became famous after her extremely emotional speech during the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau in 2005.

“Here they imprisoned my family and burnt them all. Here they took away my name and gave me a number. I was Merka Sheva no longer – I was a number. Why did they burn my people, the Jewish People! Why did they take freedom from us? Why did they give us a patch? A yellow patch? To let them know that we are Jews. Never! Never let it come back. I stood so naked in that camp. A girl… sixteen years old! I am standing here naked,” she said at the time.

The search for Janek

On 15 February 2005, “Gazeta Krakowska” published a text by Rafał Lorek entitled “Is this Janek?” In it, the author describes Jan Fiba, who as a twenty-something was a forced labourer at IG Farben and KL Birkenau. He could therefore have been the Janek sought by Merka Szewach. The man died tragically in 1972. Asked if he remembered what the results of the publication were, if there was an attempt by Merka to recognise the man, Rafał Lorek replied that it was so long ago that he did not remember. Barbara Jaworska, the author of the text “Who remembers Janek?” published in “Dziennik Polski” on 30 March 2005, also does not remember the story about Janek she described 18 years ago.

Bartosz Bartyzel, a spokesman for the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, when asked whether it was even possible to prove that any of the men reported to the museum was Janek, replied:

“Dr. Henryk Świebocki, a Museum employee who has been retired for many years, dealt with this case at the time. At that time he did not find any information that could lead to the identity of this person.”

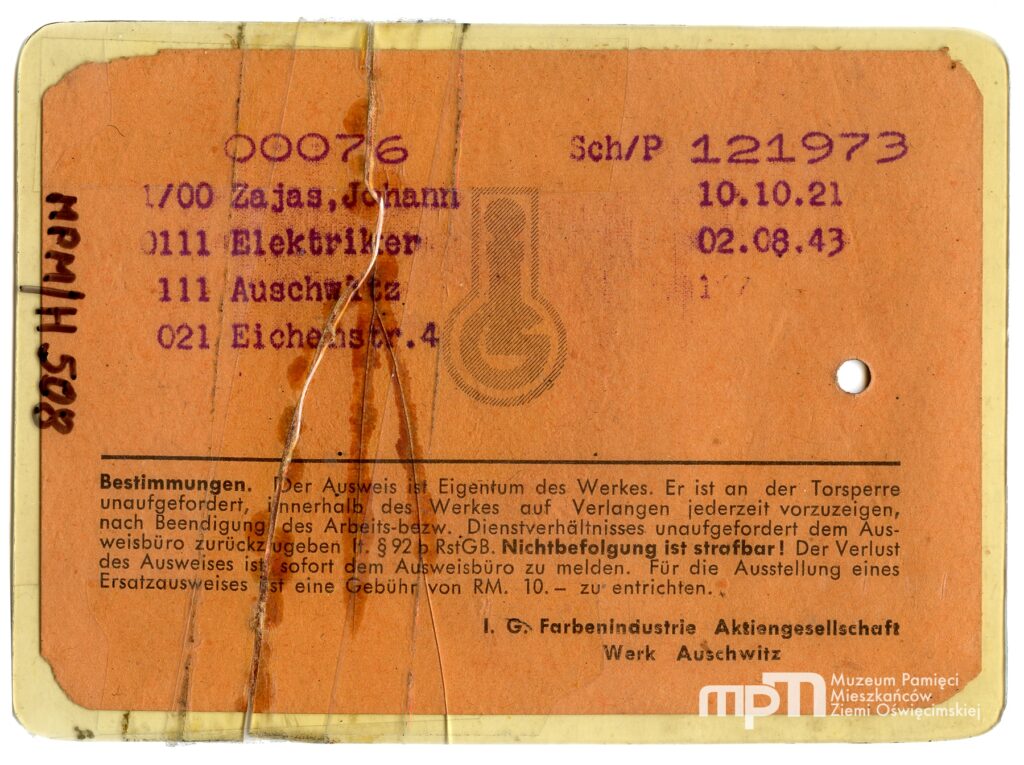

Jan Zajas

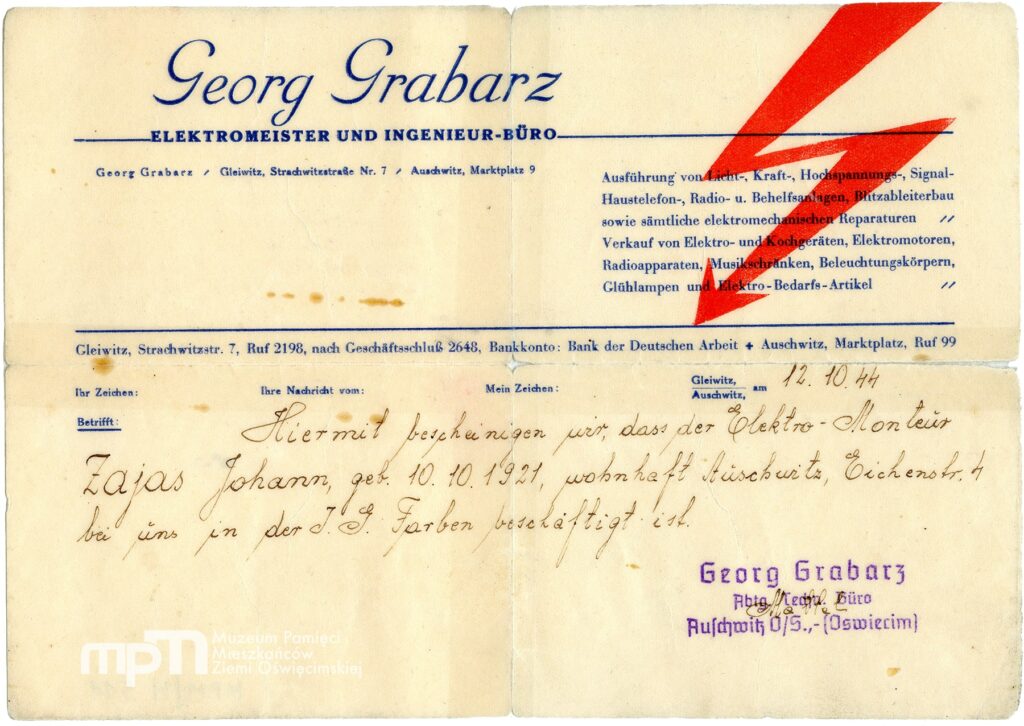

Janek’s story intrigued Teresa Bebak. This character reminded her very much of her dad. His name, age, profession, and place of residence – 0święcim – all agreed. In 1944, Jan Zajas was an electrician in the German company of Georg Grabarz from Gliwice, providing services to Germans before the establishment of Auschwitz and later during the operation of the camp.

A photograph taken during the war shows two young men. On the left, with a coiled cable on his shoulder, stands Jan Zajas, next to his friend (name unknown).

“In fact, my father never talked about helping the prisoners. Somewhere I can recall that he brought some things home for safekeeping and later my grandmother found out that the person who came to collect them was a Jew. Later, during my childhood, a parcel from Israel came to us, but times were such that it was not to be boasted about and that was the end of it. Rather, my father talked about how they would pull fast ones on the SS men. For example: when he was doing some work in Wyry and lit a cigarette and an SS man threatened him that he would be sent to Auschwitz for it, my father replied that he had just come from there, which was unthinkable for a German,” Teresa Bebak wrote in her e-mail to the Remembrance Museum. “They sat with Eugeniusz Nosal over vodka and reminisced about their camp days.” “I don’t remember the details, but there was something about leaving the camp area and using shrewd (cunning) ways. What stuck in my mind, as a child at the time, was some kind of crotchety (facetious) note to these stories which felt unnatural to me.”

Eugeniusz Nosal

The figure of Eugeniusz Nosal – prisoner of the first transport to Auschwitz No. 693 – is extremely interesting. He was born on August 19, 1911 in Nowy Sącz. He was a construction technician by profession. In Auschwitz, he worked in the construction office. Thanks to the fact that he went outside the camp, he organised help for the prisoners. He smuggled medicines, food and secret messages behind the wires. He survived Auschwitz. He was released in 1944 as a civilian worker to work for a German company. After the liberation of the camp in January 1945, he saved the “Arbeit macht frei” inscription above the camp entrance gate from being taken away by the Red Army. He was also instrumental in rescuing the “Book of Block 22B” with entries on female prisoners. Perhaps Jan Zajas’s name would appear in his memoirs?

However, a visit to the archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and an examination of the content of the statements made by Eugeniusz Nosal did not yield any new information about Janek. Nor are they to be found in Nosal’s statement found on the website zapisyterroru.pl or among the search results on the website of the International Centre for the Study of Nazi Persecution https://arolsen-archives.org/

Further searches

Let us recall that Jan Zajas worked as an electrician for Georg Grabarz’s company from Gliwice. Did this company carry out work on the Birkenau site in the second half of 1944? Could Jan Zajas have been working in the camp at that time?

I asked Szymon Kowalski of the Archives Department of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum for help.

“The participation of German companies in the construction and expansion of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp complex is documented in the Zentralbauletiung file (a large part of the originals are still stored in the archives of the Russian Federation, as is a huge file of workers).There are quite a few references to the Georg GRABARZ company in the documentation we have; also concerning work on the Birkenau Concentration Camp site (e.g. Wasserversogungsanlage – sewage network), but the dates end with 24 September 1943. Of course, it can be assumed (also on the basis of the assumption in question) that the company continued to operate here also in 1944,” wrote Szymon Kowalski in response to a question about Georg Grabarz’s company.

Jan Zajas died aged 59 in a traffic accident on 15 April 1981. He was laid to rest in the parish cemetery in Oświęcim.

The team of the Office for Former Prisoners at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum Archives had no information on the place and date of Miriam Yahav’s death. Radio Bialystok’s website only stated that she died in 2017.

The response from the Yad Vashem Institute in Israel came a day after the question was emailed.

Miriam Yahav died on 13 November 2017 at the age of 97. She was buried in the New Cemetery in Be’er Sheva, Israel.

Could Jan Zajas have been Jan helping Jewish women imprisoned in KL Birkenau? The information gathered suggests it is a possibility. But… we will never know for sure…

***

I would like to thank the staff of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum as well as the Museum of the Jews of Białystok and the Region and the Yad Vashem Institute in Israel for their kindness and assistance.

Piotr Tarczyński

piotr.tarczynski@muzeumpamieci.pl